How would a Carbon Dividend work?

The environmental benefits associated with a carbon price have been well established (see Why a Carbon Price?). In fact, many scientists and economists now point to carbon pricing as the only policy tool capable of ensuring 2050 net zero emissions targets are met (see for example Baranzini et al. (2017)). However, a carbon pricing scheme offers not only the most efficient form of emissions reduction, it also offers potential financial benefits by way of technology and market innovation, reduced climate damage and direct cash benefits in the case of a dividend redistribution scheme.

What would a carbon pricing scheme look like in Australia?

A tax is placed on the carbon content of fossil fuels at a predictably rising rate per tonne of carbon dioxide. This will apply to the 50 or so fossil fuel producers and importers. As with any form of a carbon price, the carbon tax will generate a substantial stream of revenue, which the government can choose to spend on fiscal projects, recycle into the economy, or return equally to citizens via a dividend. It is this last option—as discussed in our article Why have a dividend in a carbon price?—that CCL has long advocated for.

How would it financially benefit Australians?

To see how such a redistribution scheme could be designed and implemented, we turn to the Australian Carbon Dividend Plan (ACDP) 2018 by UNSW Economics Professor Richard Holden and Law Professor Rosalind Dixon . They model a universal carbon tax of $50 per tonne on 466 million MT of CO2 equivalent from electricity, direct combustion, transport, fugitive emissions and industrial processes leading to an estimated A$23.3 billion in generated revenue. Then, after deducting approximately 10% of revenues to cover government usage and administration costs, it is estimated that a remaining A$21.0 billion would be available for redistribution.

The ACDP proposes that this generated revenue be shared equally amongst all voting aged Australians. Using a current estimate of 16 million eligible recipients, this equates to a dividend of approximately A$1,310 each in annual, tax-free carbon dividends.

Would the dividend cover the rise in energy prices and other costs?

Let us consider a typical Australian household of two adults and two children under 18. Using data from the ABS and the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, Dixon & Holden (2018) estimate that this average Australian household would experience a 2.7%, or $2,035, increase in expenditures under the carbon tax. This rise would predominantly stem from added transport costs ($1,085) and power usage ($476). However, for this same household, the carbon dividend represents an income of approximately $2,620 per annum. Overall, this leaves them an estimated $585 per annum better off.

Most significantly, this net benefit reflects an estimate that relies on no changes in their current consumption behaviour. When accompanied by behavioural changes—such as a decrease in usage of energy intensive products and switching to low carbon products and services—it is likely that the average Australian household would experience even greater net benefits.

Addressing inequality

It is also important that we consider the equity implications under the proposed ACDP. Since low-income households receive the same per person dividend distribution but have lower total consumption and lower carbon consumption, these households are expected to benefit the most. For the 20% of Australian households reporting lowest income, increased expenditure under the carbon tax is estimated to be $1,315 per annum. Hence, the lowest income quintile households are expected to be $1,305 better off.

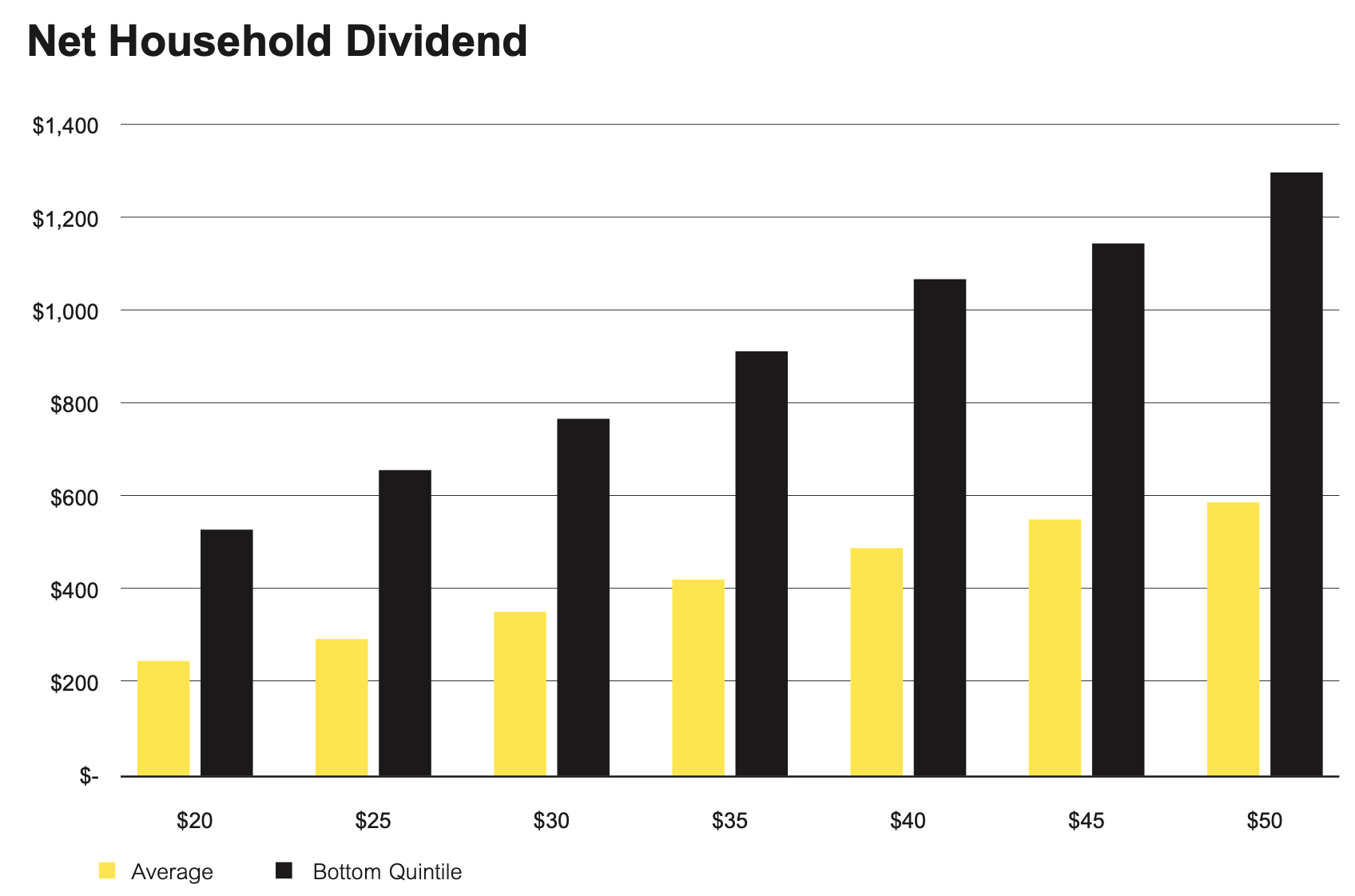

This disproportionate net benefit to lower income families holds true as the price rises. Holden & Dixon (2019) show the estimated net benefit of average and low-income households under a range of carbon prices ranging from $20 per MT to $50 per MT (Figure 2). Under all proposed tax prices, both households experience a net financial benefit, which rises as the price on carbon is increased. This modelling therefore offers validity to a phased approach in which a carbon tax is first introduced at low rate and progressively increased over time—households and the economy at large would have an opportunity to gradually adjust to the new scheme.

Figure 2: Source—Dixon & Holden (2018)

Conclusion

As Australia commits to increasingly ambitious action on climate change, it must seriously consider the most efficient way to do so and implement a carbon price. Choosing a carbon price with an effective and equitable redistribution process will not only benefit the environment and the climate, but the majority of Australian households will benefit financially and thus become more resilient to the disruptive effects of climate change. The carbon dividend has a redistributive mechanism at its centre and should be an obvious choice for policymakers.

References

Baranzini, A., van den Bergh, J.C.J.M., Carattini, S., Howarth, R.B., Padilla, E. and Roca, J. (2017), Carbon pricing in climate policy: seven reasons, complementary instruments, and political economy considerations. WIREs Clim Change, 8: e462. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.462

Dixon, R., & Holden, R. (2018). A Climate Dividend for Australians. UNSW.